Holding the Line Against Russia: Ukraine’s Strategic Prospects Without US Support – A Comprehensive Analysis

Ongoing War in Ukraine – Comprehensive Report (as of March 3, 2025)

1. Historical Background and Context

Post-Soviet Relations: After the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991, Ukraine emerged as an independent state and sought to forge its own path. Over the next two decades, Ukraine oscillated between pro-Russian and pro-Western leadership. Tensions grew as Ukraine pursued closer ties with the European Union and NATO, which Russia vehemently opposed (Timeline: The events leading up to Russia's invasion of Ukraine | Reuters) (Ukraine: Conflict at the Crossroads of Europe and Russia | Council on Foreign Relations). A key moment came in 2008, when NATO promised that Ukraine would eventually join the alliance, angering Moscow (Timeline: The events leading up to Russia's invasion of Ukraine | Reuters). Internally, Ukraine was divided – western regions favored European integration while eastern and southern regions (with many Russian speakers) leaned toward Russia (Ukraine: Conflict at the Crossroads of Europe and Russia | Council on Foreign Relations) (Ukraine: Conflict at the Crossroads of Europe and Russia | Council on Foreign Relations). This tug-of-war set the stage for future conflict.

Euromaidan and 2014 Escalation: In late 2013, Ukraine’s pro-Russian president, Viktor Yanukovych, abruptly rejected an EU association agreement, sparking mass pro-European “Euromaidan” protests in Kyiv (Conflict in Ukraine: A timeline (2014 - eve of 2022 invasion) - House of Commons Library) (Timeline: The events leading up to Russia's invasion of Ukraine | Reuters). The unrest toppled Yanukovych in February 2014, prompting Moscow to act. Within days, masked Russian forces seized Crimea, and Russia unilaterally annexed the Crimean peninsula in March 2014 – the first forcible annexation in Europe since World War II (Conflict in Ukraine: A timeline (2014 - eve of 2022 invasion) - House of Commons Library) (Timeline: The events leading up to Russia's invasion of Ukraine | Reuters). Around the same time, pro-Russian separatists in eastern Ukraine’s Donbas region (Donetsk and Luhansk) declared “independence,” with covert Russian backing. This triggered an armed conflict between Ukrainian forces and separatists through 2014–2021, resulting in some 14,000–15,000 deaths (Timeline: The events leading up to Russia's invasion of Ukraine | Reuters) (Ukraine: Conflict at the Crossroads of Europe and Russia | Council on Foreign Relations). Multiple ceasefire accords (Minsk agreements) froze but did not resolve the Donbas war. Tensions remained high, and Russia continued to view Ukraine’s westward drift as a threat to its interests.

Prelude to Invasion (2021–2022): In 2021, Russia began massing troops near Ukraine’s borders under the guise of “exercises.” By December 2021, Moscow issued sweeping security demands – insisting NATO never admit Ukraine and that the alliance pull back forces from Eastern Europe – effectively seeking to reassert a sphere of influence (Timeline: The events leading up to Russia's invasion of Ukraine | Reuters). These ultimatums were rejected by the United States and NATO, who upheld NATO’s “open door” policy (Timeline: The events leading up to Russia's invasion of Ukraine | Reuters). Diplomatic efforts faltered, and in February 2022 Russian President Vladimir Putin openly questioned Ukraine’s legitimacy as a state, while recognizing the Moscow-backed Donbas separatist authorities as “independent” (Timeline: The events leading up to Russia's invasion of Ukraine | Reuters). Days later, on February 24, 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine from multiple fronts.

2. Chronological Timeline of Major Events (Feb 2022 – Mar 2025)

Feb 24, 2022 – Invasion Begins: Russia invades Ukraine from the north (via Belarus), east (Donbas), and south (Crimea), in what Putin calls a “special military operation.” The offensive’s initial goal is a lightning strike to seize Kyiv and overthrow Ukraine’s government within days (Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, February 24, 2025 | Institute for the Study of War). In response, Ukraine declares martial law and general mobilization, defending fiercely.

Mar–Apr 2022 – Battle for Kyiv and Northern Ukraine: Russian forces advance toward Kyiv and other northern cities but encounter strong Ukrainian resistance and logistical woes. By early April, Russia’s offensives in northern Ukraine collapse – Ukrainian forces defend Kyiv and Russian troops retreat completely from Kyiv, Chernihiv, and Sumy regions. In areas they occupied, evidence emerges of apparent war crimes (e.g. Bucha massacre of civilians), sparking global outrage (U.N. rights office cites growing evidence of war crimes in Ukraine | Reuters) (U.N. rights office cites growing evidence of war crimes in Ukraine | Reuters). With the northern front abandoned, Russia refocuses on the eastern Donbas and southern coast.

Apr–July 2022 – Eastern and Southern Battles: Russia unleashes a brutal bombardment in Donbas. Heaviest fighting shifts to the Siege of Mariupol, a strategic port in the south. After weeks of urban combat and indiscriminate shelling, Mariupol falls to Russian forces in May, at the cost of thousands of civilian lives. In the east, Russia slowly captures the cities of Severodonetsk and Lysychansk by July, bringing nearly all of Luhansk oblast under Russian control. However, these gains come at a high cost to Russia’s military. Meanwhile, Western countries begin supplying Ukraine with heavier weapons; by summer, US-supplied HIMARS rocket systems help Ukraine strike Russian ammunition depots and slow the Russian advance.

Sept 2022 – Ukrainian Counteroffensive in Kharkiv: In a stunning reversal, Ukraine launches a rapid counteroffensive in the northeastern Kharkiv region, liberating about 8,000 km² of territory in a matter of days. Dozens of towns (including Izium and Kupiansk) are retaken, and Russian frontlines in the northeast collapse. This marks a major turning point, showcasing Ukraine’s ability to reclaim occupied land (Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, February 24, 2025 | Institute for the Study of War). Simultaneously, Putin hastily announces “referendums” in occupied Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia, and Kherson, aiming to legitimize Russian annexation of these regions.

Sept–Oct 2022 – Annexation and Escalation: Between September 23–27, the Kremlin-stage pseudo-referendums in the four occupied oblasts (amid international condemnation). On Sept 30, 2022, Putin signs documents claiming to annex Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson, and Zaporizhzhia into Russia – despite not fully controlling these territories. The United Nations General Assembly overwhelmingly condemns this “attempted illegal annexation” as void and affirms Ukraine’s sovereignty within its internationally recognized borders (United Nations condemns Russia's move to annex parts of Ukraine | Reuters) (United Nations condemns Russia's move to annex parts of Ukraine | Reuters). In response, Ukraine formally applies for accelerated NATO membership. Fighting intensifies: Ukraine presses in the east while Russia retaliates with a mass missile barrage on Ukrainian cities and infrastructure in October (including Kyiv), signaling a new phase of air raids on civilian targets.

Nov 2022 – Liberation of Kherson: After months of Ukrainian pressure on the southern front (using HIMARS to cut bridges and supply lines), Russia’s position west of the Dnipro River becomes untenable. On November 11, 2022, Russian forces retreat from Kherson city and the entire west-bank of Kherson oblast, allowing Ukraine to reclaim the only provincial capital Russia had captured. This Ukrainian victory – achieved without urban combat – further shifts momentum (Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, February 24, 2025 | Institute for the Study of War). By year’s end, front lines stabilize roughly along the Dnipro in the south and a tense stalemate sets in across the Donbas front.

Winter 2022–2023 – War of Attrition: Through the winter, Russia switches to a strategy of attacking Ukraine’s energy infrastructure, aiming to break civilian morale. Waves of missile and drone strikes repeatedly knock out power across Ukraine, causing blackouts and hardship during freezing months. Despite this, Ukrainian resolve remains high. On the battlefield, Bakhmut, a city in Donetsk, becomes the focal point of intense fighting. Russian Wagner Group mercenaries and Ukrainian defenders engage in a grinding battle for Bakhmut that drags on for months, inflicting heavy casualties on both sides. By early 2023, the front line moves only slowly, with Bakhmut dubbed the war’s longest and bloodiest engagement (Russia's Prigozhin claims capture of Bakhmut, Ukraine says fighting goes on | Reuters).

Spring–Summer 2023 – Counteroffensive and Setbacks: In May 2023, Russia’s Wagner forces claim to have finally captured most of Bakhmut, though Ukraine retains positions on the city’s flanks (Russia's Prigozhin claims capture of Bakhmut, Ukraine says fighting goes on | Reuters). Shortly after, in June 2023, Ukraine launches a long-anticipated counteroffensive in the south (Zaporizhzhia front) and east. Armed with newly delivered Western tanks and armored vehicles, Ukraine attacks Russian fortified lines in areas like Melitopol direction and south of Bakhmut. Progress proves slower and more difficult than in 2022, as Russian troops had months to dig into defensive trenches and lay extensive minefields. Ukraine makes incremental gains – liberating villages such as Robotyne by August – but does not achieve a decisive breakthrough before the fall rains set in. In June 2023, an explosion breaches the Kakhovka Dam (in Russian-occupied Kherson), causing massive flooding along the Dnipro; Ukraine and Russia blame each other for the dam’s destruction, and thousands are displaced in the humanitarian disaster.

June 2023 – Wagner Mutiny in Russia: In a dramatic episode highlighting cracks in Russia’s war effort, Yevgeny Prigozhin – leader of the Wagner mercenary group – stages a short-lived mutiny on June 24, 2023. His forces seize a military hub in Rostov-on-Don and advance toward Moscow, protesting Russia’s military leadership. The revolt is abruptly called off within 24 hours via a deal with the Kremlin. While this Wagner mutiny ends without direct impact on the front, it exposes turmoil in Putin’s system during the war’s second year.

Autumn 2023 – Stalemate and Drone Warfare: By late 2023, the conflict increasingly resembles a war of attrition. Russia launches a fierce assault to encircle Avdiivka (a fortified Ukrainian-held city in Donetsk) in October, but Ukrainian forces hold the lines. Both sides turn more to drone warfare – Ukraine strikes airbases and supply lines in Russian-occupied Crimea and even within Russia’s border regions, while Russia continues kamikaze drone attacks on Ukrainian cities. The Black Sea Grain Deal, which had enabled Ukraine to export grain via Odesa ports despite the war, collapses in July 2023 after Russia refuses to renew it, contributing to renewed concerns about global food security.

2024 – A Deadly Stalemate: As the war enters its third year, neither side achieves a decisive advantage. Throughout 2024, fighting rages primarily along the eastern front (especially around Bakhmut, Avdiivka, and the Kreminna–Svatove sector in Luhansk) and the southern front (Zaporizhzhia oblast towards Tokmak and Melitopol). Russia makes small gains in some areas while fortifying its defense lines, and Ukraine continues local offensives aimed at wearing down Russian positions. By early 2024, Russia still holds most of the territory it seized in the initial invasion, whereas Ukraine has liberated roughly half of those lands (Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, February 24, 2025 | Institute for the Study of War) (Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, February 24, 2025 | Institute for the Study of War). Both militaries are increasingly strained – Russia resorts to additional mobilization and austerity measures to sustain the war, and Ukraine awaits further deliveries of advanced Western weapons (including promised F-16 fighter jets) to invigorate its campaigns.

Early 2025 – Status Quo Persists: By February 2025, the front line has not dramatically moved for months. Russia and its proxies occupy roughly 20% of Ukraine’s territory, including Crimea and parts of Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia, and Kherson regions (War in Ukraine | Global Conflict Tracker). No peace agreement is in sight, despite various international efforts. The war has become a grueling stalemate, yet both Kyiv and Moscow remain unwilling to concede their core aims, setting the stage for a protracted conflict.

3. Current Territorial Status

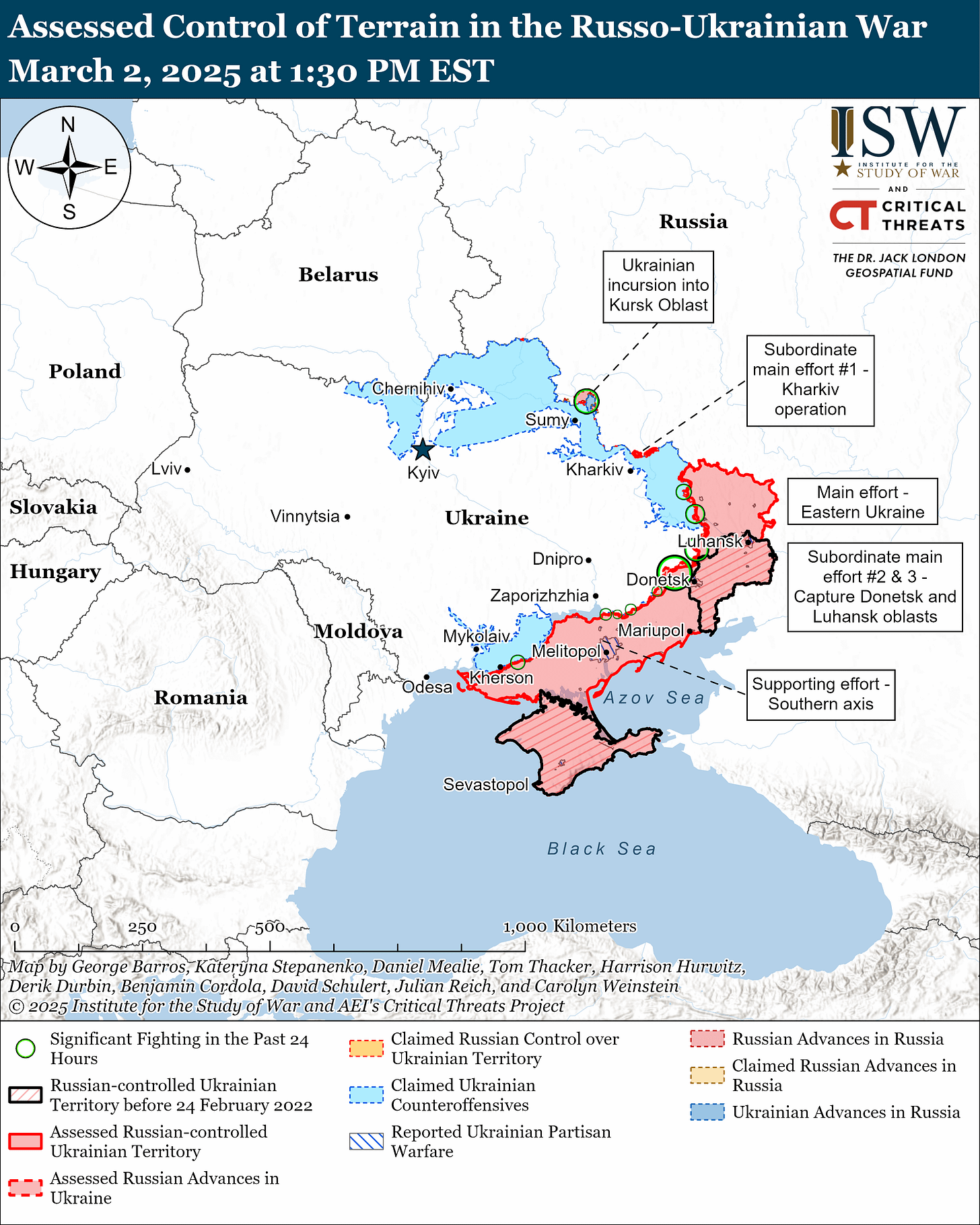

Territorial Control (March 2025): As of today, Russian forces control large portions of eastern and southern Ukraine, while the rest of the country (roughly 80%) remains under Ukrainian government control. Russia’s occupation includes the entire Crimean Peninsula (annexed in 2014) and extensive areas of the Donbas and coastal south. In the east, virtually all of Luhansk province and about half of Donetsk province are under Russian occupation. In the south, Russian forces hold the majority of Zaporizhzhia oblast (including the vicinity of Melitopol and the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant in Enerhodar) and the eastern bank of Kherson oblast along the Dnipro River. Ukraine, for its part, retains control of key cities such as Kharkiv, Dnipro, Zaporizhzhia city, Mykolaiv, and Odesa, and it has liberated territories in the north-east (Kharkiv region) and north of Kherson that were occupied in 2022. The front line now stretches over 1,000 km from the north-east down to the south, marked by trenches and fortifications.

Approximate Occupied Area: Russia currently occupies an estimated 18–20% of Ukraine’s internationally recognized territory (about 115,000–125,000 square kilometers) (War in Ukraine | Global Conflict Tracker). This includes the Crimean Peninsula and parts of five Ukrainian oblasts. Notably, this is a smaller share than in March 2022, thanks to Ukrainian counteroffensives that recaptured roughly half of the land initially overrun by Russia (Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, February 24, 2025 | Institute for the Study of War). However, the areas still under Russian control are strategically important to Moscow – providing a “land bridge” from mainland Russia to Crimea and encompassing most of Ukraine’s industrial Donbas region.

Dynamic Frontlines: The situation on the ground remains fluid in certain sectors. In Donetsk oblast, fierce fighting continues around hotspots like Bakhmut, Avdiivka, and Maryinka, where frontlines have shifted back and forth incrementally. In southern Ukraine, Ukrainian forces have established a foothold on the east bank of the Dnipro in a few locations and continue limited attacks toward Tokmak and Melitopol, but Russia still controls the main routes to Crimea. No major cities (aside from those in Donbas) are currently under imminent threat of capture, and the conflict has largely settled into a positional war. Both sides regularly launch small-scale offensives and artillery duels along the contact line, but large territorial changes have been rare since late 2022.

Maps: The map above highlights the areas of continuous Ukrainian control (in yellow) versus areas under Russian control (red). The light blue zones indicate territory that Ukraine has liberated during counteroffensives (e.g. parts of Kharkiv and Kherson). As shown, Russia’s grip is concentrated in the border-adjacent east and the land corridor to Crimea. Internationally, these Russian-held regions are still recognized as sovereign Ukrainian territory – underscored by U.N. resolutions rejecting Russia’s annexation claims (United Nations condemns Russia's move to annex parts of Ukraine | Reuters). Ukraine has no de facto authority in occupied areas, where Moscow has installed proxy administrations and introduced the Russian ruble and law. Meanwhile, Ukraine administers the rest of the country, including all of Kyiv, central and western Ukraine, and areas around major cities like Kharkiv and Odesa that were at one point under direct attack but never fell.

4. Strategic Analysis of the Conflict

Russian Objectives and Strategy: Russia’s strategic war aims have evolved since the initial invasion. At the outset, Moscow’s goal was regime change in Kyiv – to decapitate Ukraine’s leadership, install a pro-Russian government, and effectively end Ukraine’s independent statehood (The Russo-Ukrainian War: A Strategic Assessment Two Years into the Conflict | AUSA). Putin framed this as the “demilitarization and denazification” of Ukraine. This maximalist aim failed when the Kremlin’s blitz on Kyiv was repelled in March 2022. Russia then narrowed its objectives to more attainable ends: seizing and holding enough Ukrainian territory to fracture the Ukrainian state and secure a land corridor to Crimea (The Russo-Ukrainian War: A Strategic Assessment Two Years into the Conflict | AUSA) (The Russo-Ukrainian War: A Strategic Assessment Two Years into the Conflict | AUSA). In September 2022, Putin claimed to annex four Ukrainian regions, signaling an intent to permanently absorb Donbas and southern Ukraine into Russia. Strategically, Moscow seeks to maintain these territorial acquisitions to use as leverage for any “acceptable” political outcome – whether formal annexation or forcing Kyiv into neutrality. By late 2023, recognizing its military limitations, Russia settled into a war of attrition aiming to outlast Ukraine and its supporters. The Kremlin’s current strategy is to grind down Ukraine’s military, devastate its economy, and exhaust Western patience, betting that if it can make the war last long enough, Ukraine’s ability to resist will erode (The Russo-Ukrainian War: A Strategic Assessment Two Years into the Conflict | AUSA). In essence, Putin appears to be playing for time – entrenching his gains, mobilizing more manpower, and hoping that political shifts (like wavering U.S. support or European fatigue) will tip the balance in Russia’s favor.

Ukrainian Objectives: Ukraine’s war aims are straightforward – to defend its sovereignty and restore control over all its territory. President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has consistently rejected any peace deal that involves ceding land. Ukraine’s focus remains on liberating all areas under Russian occupation, including Donbas and Crimea, to reassert its 1991 borders (The Russo-Ukrainian War: A Strategic Assessment Two Years into the Conflict | AUSA). In Kyiv’s view, anything short of full restoration of territorial integrity would reward Russian aggression and undermine Ukraine’s long-term security. Additionally, Ukraine seeks to deepen its integration with Western structures (e.g. the EU and NATO) as a guarantee against future aggression. Strategically, Ukraine knows it cannot easily conquer Russia militarily, but it aims to make continued Russian occupation untenable by inflicting maximal losses and leveraging international isolation of Moscow. Ultimately, Kyiv’s end state is a free, independent Ukraine with secure borders – ideally buttressed by international security guarantees or alliance membership – and a weakened Russia compelled to retract its expansionist ambitions.

Military Strategies and Tactics: Over the past two years, the conflict has showcased starkly different military approaches:

Russian Tactics: Russia has leveraged its advantage in sheer firepower and manpower to wage a war of attrition. Its forces resort to heavy artillery bombardments and air strikes to pulverize targets before attempting advances. This was seen clearly in the sieges of Mariupol and Severodonetsk in 2022 and the meat-grinder assault on Bakhmut in 2023. Russian units often adopted “wave” attacks – throwing large numbers of mobilized infantry or Wagner mercenaries into battle to probe Ukrainian lines, at enormous cost in lives. The Russian military has demonstrated a high tolerance for casualties in exchange for slow territorial gains (Russia's Prigozhin claims capture of Bakhmut, Ukraine says fighting goes on | Reuters). Additionally, Russia has increasingly targeted civilian infrastructure (power grids, railways, ports) with long-range missiles and Iranian-made drones to sap Ukraine’s economic resilience and terrorize its population. Defensively, since mid-2022 Russia dug an extensive network of trenches, minefields, and dragon’s teeth fortifications along the front, which significantly slowed Ukraine’s 2023 counteroffensive. In summary, Moscow’s operational approach emphasizes brute force and attrition over maneuver – seeking to batter the Ukrainian army into collapse, even if it means destroying towns and sacrificing thousands of its own soldiers for minimal gains. This attritional strategy achieved some localized successes (like the eventual capture of Bakhmut), but it has also badly degraded Russia’s army. Western analysts note that by expending vast resources for small advances, Russia’s military has suffered losses that are likely unsustainable in the long term (Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, February 24, 2025 | Institute for the Study of War) (Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, February 24, 2025 | Institute for the Study of War).

Ukrainian Tactics: In contrast, Ukraine has maximized agility, superior battlefield intelligence, and precision weaponry to offset Russia’s numerical advantages. Ukrainian forces have adopted a defense-in-depth when on the defensive – ceding ground slowly to absorb Russian attacks, then counterattacking when the enemy is overextended. During Russia’s Kyiv offensive, for example, lightly armed volunteer units ambushed Russian columns with anti-tank missiles, exploiting local knowledge and mobility to stall a vastly larger force. As the war progressed, Ukraine became increasingly adept at “combined arms” operations using Western-provided equipment. Notable was its use of U.S.-supplied HIMARS precision rocket systems starting summer 2022 to destroy Russian ammunition depots, command posts, and bridges far behind the front line. This struck at Russia’s logistics and helped set up Ukraine’s successful counteroffensives. Ukraine’s military has also been innovative and adaptive: it developed cheap long-range drones to hit targets deep in Crimea and Russia, and used small unit tactics to penetrate Russian lines in Kharkiv. During the 2023 counteroffensive, rather than a single massive assault, Ukraine probed for weak points along the front and then concentrated forces (including Western tanks like Leopards) where it made incremental progress. A hallmark of Ukraine’s approach is integrating modern technology and intelligence with traditional ground maneuvers. For example, real-time satellite and drone surveillance is used to direct artillery strikes with high accuracy, compensating for Russia’s greater volume of fire. Ukrainian forces are also employing innovative battlefield tech – from anti-drone electronic warfare to secure communications – giving them a “technological edge” in certain engagements (Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, February 24, 2025 | Institute for the Study of War). However, Ukraine remains heavily dependent on Western supplies for ammunition, advanced air defenses, and replacements for equipment losses. Ukrainian troops are highly motivated and skilled, but Ukraine’s smaller population means it must be more judicious with manpower than Russia. Overall, Ukraine’s strategy has been to stay on the offensive when possible (to keep Russia off balance) while shielded by ever-improving defensive systems (like NASAMS and Patriot batteries against air attacks). This approach, combined with Western training, enabled feats such as the Kharkiv blitz. But as seen in late 2023, breaching heavily fortified Russian lines without air superiority is exceedingly difficult, so Ukraine’s progress has been modest lately.

⠀Key Battles and Offensives: Several major operations illustrate these strategic dynamics:

Battle of Kyiv (Feb–Mar 2022): A rapid Russian thrust toward Kyiv was defeated by Ukrainians employing mobile anti-tank teams and exploiting Russia’s logistical overextension. This victory saved the capital and marked Russia’s first major strategic failure (Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, February 24, 2025 | Institute for the Study of War).

Siege of Mariupol (Mar–May 2022): Russian forces encircled and relentlessly bombarded the port city of Mariupol, eventually forcing its outgunned Ukrainian defenders to surrender. Russia achieved a land corridor to Crimea by taking Mariupol, but at the cost of destroying the city and tying down forces for three months.

Donbas Battles (Summer 2022): Russia concentrated forces in Luhansk and Donetsk, grinding forward behind massive artillery barrages. They captured Severodonetsk and Lysychansk, expelling Ukrainian forces from Luhansk province, but Russian advances stalled afterward as their units became exhausted and depleted.

Kharkiv Counteroffensive (Sept 2022): Ukraine’s lightning operation in Kharkiv province re-took vast swathes of territory with minimal resistance, as Russian lines collapsed. This offensive demonstrated superior Ukrainian planning, surprise, and maneuver – and the effective use of Western intelligence and long-range strikes to isolate the battlefield.

Kherson Campaign (Summer–Fall 2022): Ukraine methodically targeted bridges and supply nodes on the Dnipro River, isolating Russian troops in west-bank Kherson. Under pressure, Russia withdrew in November without a fight in Kherson city. Ukraine’s patient, systematic approach avoided a bloody urban battle and reclaimed a vital region (Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, February 24, 2025 | Institute for the Study of War).

Battle of Bakhmut (Aug 2022 – May 2023): On the offensive, Russia (led by Wagner mercenaries) spent many months and tens of thousands of shells to capture the small city of Bakhmut. Ukraine turned Bakhmut into a kill zone, using it to attrit Russian units, even as it eventually lost most of the city. By the end, Bakhmut epitomized the war’s high cost – with block-by-block fighting resulting in enormous losses for a very limited Russian gain (Russia's Prigozhin claims capture of Bakhmut, Ukraine says fighting goes on | Reuters).

Ukrainian Summer Counteroffensive (June–Oct 2023): Armed with newly delivered Western tanks, Ukraine attacked entrenched Russian positions in the south (Zaporizhzhia) and also around Bakhmut’s flanks. Progress was slow due to dense minefields and stout Russian defenses. Ukraine managed to liberate some villages and breach Russia’s first defensive line in places, but not the strategic breakthrough it hoped for. This showed that while Western armor and training improved Ukraine’s capabilities, Russian defenses (and lack of air power for Ukraine) made offensive operations extremely challenging.

⠀In sum, Russia’s military strategy has shifted to holding on to territory and inflicting maximum attrition, while Ukraine’s strategy is to steadily erode the Russian occupying forces and take back land where opportunities arise. Neither side has been able to land a knockout blow. Analysts assess that Russia’s conventional military is substantially weakened after its setbacks, yet it remains dangerous and in possession of critical areas. Ukraine has surprised the world with its effective defense and counterattacks, but it faces material fatigue and relies on external support to sustain its war effort (Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, February 24, 2025 | Institute for the Study of War) (Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, February 24, 2025 | Institute for the Study of War). As of early 2025, the conflict has essentially become a stalemate of wills and logistics – with each side hoping the other breaks first.

5. International Involvement and Global Response

Western Support (U.S., NATO, EU): From the outset of the invasion, the United States, NATO allies, and the European Union have strongly backed Ukraine. Western nations have supplied unprecedented levels of military aid, financial assistance, and intelligence sharing to bolster Ukraine’s defense. The United States is the single largest donor: as of 2024, it had committed over $70–75 billion in military, economic, and humanitarian aid to Ukraine (Opinion: Could Ukraine survive a JD Vance vice presidency?). U.S.-supplied weaponry – Javelin anti-tank missiles, HIMARS rocket systems, M777 howitzers, NASAMS air defenses, and more recently Patriot missiles, Abrams tanks, and promised F-16 fighter jets – have been pivotal in strengthening Ukraine’s capabilities. Washington also leads the Ukraine Defense Contact Group (an alliance of 50 countries) coordinating arms deliveries from NATO members and other partners. NATO, as an organization, is not directly intervening militarily in Ukraine (to avoid a direct NATO-Russia war), but individual NATO countries (such as Poland, the UK, the Baltic states, Germany, France, Canada, etc.) are providing significant aid. European Union institutions have offered tens of billions in macro-financial loans and grants to keep Ukraine’s economy afloat. In fact, when combining contributions, European countries collectively have provided more total aid than the U.S. (including substantial packages from the EU, UK, Germany, etc.) (Opinion: Could Ukraine survive a JD Vance vice presidency?~). This includes advanced European weapons like German Leopard 2 tanks, British Challenger 2 tanks, French CAESAR artillery, Polish Krab howitzers, and others being delivered to Ukraine’s army. NATO has also boosted its own eastern flank defenses – deploying additional battlegroups to member states bordering Ukraine/Russia – to deter any spillover. Politically, Western leaders have unanimously condemned Russia’s aggression. They imposed sweeping sanctions (see below) and moved diplomatically to isolate Moscow. The war has even prompted historic shifts in European security policy: Finland and Sweden abandoned decades of neutrality to seek NATO membership (Finland joined NATO in April 2023, and Sweden is in the accession process) as a direct consequence of Russia’s invasion. The consistent refrain from the West has been that it will support Ukraine “for as long as it takes” to preserve its sovereignty. This strong Western unity has been a critical factor in enabling Ukraine to resist a much larger aggressor.

Global Political Stances:

European Union: The EU has emerged as a key political and economic pillar of support for Ukraine. It granted Ukraine candidate status for EU membership in June 2022 – a powerful symbol of long-term commitment to integrating Ukraine with Europe. The European Commission and member states have coordinated multiple sanctions packages against Russia (now numbering 10+ rounds of sanctions). The EU also activated its Civil Protection Mechanism to aid Ukrainian refugees and pledged funds for Ukraine’s reconstruction. However, within the EU, a few states (Hungary in particular) have been more ambivalent – Hungary has delayed some EU sanctions and aid decisions, given its leadership’s closer ties to Moscow. Nonetheless, the EU as a whole remains firmly aligned with Ukraine, providing everything from fuel and generators to a military training mission that aims to train 30,000 Ukrainian soldiers. European nations geographically closer to the conflict (Poland, the Baltic states, Nordics) have been especially forward-leaning, sending a high percentage of their defense budgets in aid and taking in millions of refugees. In sum, the war has galvanized the EU to take on a stronger foreign policy and security role.

United States and Canada: The U.S. has not only led militarily but also shaped the international diplomatic response. President Biden visited Kyiv in February 2023 in a dramatic show of support. The U.S. and Group of Seven (G7) partners have coordinated closely on sanctions, and the U.S. Congress (in bipartisan votes through 2022–23) approved tens of billions in aid packages. By 2025, there are debates in Washington about the sustainability of aid, but for now the U.S. maintains that supporting Ukraine is critical to upholding the international order. Canada, for its part, has also given significant military aid (including artillery and armored vehicles) and taken in many Ukrainian refugees. Both the U.S. and Canada have also designated Russia’s actions (such as deliberate atrocities) as war crimes, pressing for accountability. NATO as a whole, at the 2023 Vilnius summit, reiterated that Ukraine will eventually become a member, albeit without a clear timeline, and created new forums (like a NATO-Ukraine Council) to deepen cooperation short of full membership.

China: China’s stance has been officially one of neutrality, but in practice it tilts toward Russia (short of violating sanctions). Beijing has called for a ceasefire and peace talks, positioning itself as a potential mediator. In February 2023, China released a 12-point “peace proposal” calling for respect for sovereignty and addressing Russia’s security concerns – which was met with skepticism in the West as it echoed Russian talking points and did not demand Russian withdrawal from occupied land. China has refused to condemn Russia’s invasion in U.N. votes and has amplified Russian narratives blaming NATO expansion for the war. Economically, China has become an even more crucial partner for Moscow since the war: Sino-Russian trade hit record levels as China buys discounted Russian oil and gas and supplies Russia with many goods (electronics, vehicles, etc.) that Western sanctions restrict (How Sanctions Have Reshaped Russia’s Future). There have been U.S. reports that Chinese firms provided dual-use technologies (like drone components and semiconductors) to Russia, though Beijing denies supplying weapons. Essentially, China is helping Russia cushion the blow of Western isolation, all while maintaining plausible deniability. That said, China also publicly insists on opposing nuclear threats and has not recognized Russia’s annexation of Ukrainian territories. Beijing’s interest lies in supporting Russia enough to bog down the West, but not so openly as to trigger sanctions on China itself. This careful straddle was evident when China’s top leader Xi Jinping visited Moscow in March 2023 to reaffirm the China-Russia partnership, yet around the same time spoke with Zelenskyy by phone for the first time since the war, trying to preserve an image of a peacemaker.

Other Key Players: Turkey (a NATO member) has played a complex role – supplying Ukraine with Bayraktar TB2 drones that were very effective in early 2022, yet also retaining cordial ties with Moscow. Turkey brokered the U.N.-backed Black Sea Grain Initiative in July 2022, which allowed the safe export of over 30 million tons of Ukrainian grain via the Black Sea until Russia halted the deal in mid-2023. Turkish President Erdoğan has positioned himself as a mediator, hosting talks and prisoner exchanges, while also benefiting economically (through trade and energy deals) by not joining Western sanctions. Belarus, Russia’s ally, allowed its territory to be used as a staging ground for Russian forces attacking Kyiv and continues to host Russian troops and missiles. Belarus has thus been an accomplice in the war, though its own army hasn’t overtly entered the fighting. Iran has become a notable supporter of Russia by supplying hundreds of Shahed-136 kamikaze drones that Russia used to strike Ukrainian cities (U.N. rights office cites growing evidence of war crimes in Ukraine | Reuters). In return, Russia has likely promised Iran advanced weapons or financial incentives. North Korea has also voiced strong support for Russia (one of only a few countries to recognize Russia’s annexation claims) and has reportedly supplied artillery shells and rockets to the Russian army, according to U.S. intelligence. Many countries in the Global South (Asia, Africa, Latin America) have taken a more neutral stance: they voted in U.N. resolutions condemning the invasion, but they have largely avoided joining sanctions against Russia. Nations like India and Brazil call for dialogue and continue to do business with Russia (India, for example, sharply increased its imports of discounted Russian oil, undermining Western efforts to cut Moscow’s energy revenue). These countries often cite their own economic interests and skepticism of Western foreign policy, and resent being pressured to take sides. Still, global opinion overall has mostly been against Russia’s war – illustrated by U.N. General Assembly votes where over 140 countries affirmed support for Ukraine’s sovereignty (United Nations condemns Russia's move to annex parts of Ukraine | Reuters).

⠀International Sanctions on Russia: A cornerstone of the global response has been an unprecedented sanctions regime aimed at pressuring Russia to stop its aggression. Western nations (the U.S., EU, UK, Canada, Japan, Australia and others) moved within days of the invasion to impose severe economic penalties on Russia. These include:

Financial Sanctions: Russia’s central bank had about $300 billion of its foreign currency reserves frozen by Western governments (How Sanctions Have Reshaped Russia’s Future), cutting off roughly half of Putin’s war chest. Major Russian banks were cut from the SWIFT international payment system. About 70% of the Russian banking sector (by assets) is now under sanctions (How Sanctions Have Reshaped Russia’s Future). This caused an initial financial shock – the ruble’s value plummeted in early 2022 and the central bank had to impose capital controls and jack up interest rates.

Trade and Export Bans: Western countries have banned the export to Russia of high-tech components, semiconductors, aerospace equipment, and oil/gas extraction technology. These export controls aim to cripple key industries (like defense and aviation) and have forced Russia to scrounge for alternate suppliers. As a result, Russia has struggled to produce certain advanced weapons; for instance, found in destroyed Russian military equipment were foreign-made microchips not easily replaceable under sanctions (How Sanctions Have Reshaped Russia’s Future). Import restrictions and the exodus of Western companies from Russia have also led to shortages of consumer goods and spare parts.

Energy Sanctions: Europe, previously Russia’s largest energy market, drastically reduced its reliance on Russian fuel. The EU banned Russian coal imports in August 2022 and then banned seaborne imports of Russian crude oil in December 2022 (with an exemption for oil via pipeline). In 2023, the EU also banned virtually all imports of Russian refined petroleum products. Meanwhile, the G7 imposed a global price cap mechanism: insurers and shippers (many of which are Western) can only facilitate Russian oil exports if the oil is sold below a certain price ($60 per barrel for crude). This effectively forces Russia to sell its oil at a discount to buyers like India and China, cutting into Moscow’s revenue. By 2023, Russia’s gas deliveries to Europe – once its biggest source of income – had dwindled to a fraction of pre-war levels (after pipeline cut-offs and Europe finding other suppliers). These energy sanctions took time to implement but are squeezing Russia’s earnings: by early 2023, Russia’s oil and gas revenues had fallen significantly compared to the prior year.

Individual and Sectoral Sanctions: Over 1,500 Russian individuals (Putin, oligarchs, officials) and entities have been sanctioned – subject to asset freezes and travel bans. This includes freezing luxury assets (yachts, real estate) of Kremlin-linked billionaires worldwide. Entire sectors like Russian defense firms are under sanctions. Export of military or dual-use goods to Russia by anyone is prohibited, driving Russia to rely on pariah states or illicit networks.

⠀The cumulative impact of these measures has been historically severe. Russia has now overtaken Iran and North Korea as the world’s most sanctioned country, with over 16,000 sanctions measures in place by 2024 (How Sanctions Have Reshaped Russia’s Future). These sanctions have caused Russia’s economy to contract (GDP fell about 2.1% in 2022) and forced the Kremlin to prop it up through extraordinary means (How Sanctions Have Reshaped Russia’s Future). Moscow has had to undertake a wholesale reorientation of its trade – increasing commerce with China, Turkey, and other non-Western markets to compensate for lost European trade. Complex illicit trade networks have emerged for evading sanctions (for example, rerouting restricted goods through third countries), which Western authorities are actively trying to crack down on (How Sanctions Have Reshaped Russia’s Future) (How Sanctions Have Reshaped Russia’s Future). Sanctions have also compelled Russia to shift into a wartime economy – prioritizing military production at the expense of consumer goods and long-term investment. The result has been surging prices and strain on industries: inflation in Russia spiked and remains high, prompting Russia’s central bank to raise interest rates to 21% as of early 2025 to stabilize the ruble (How Sanctions Have Reshaped Russia’s Future). The exodus of foreign businesses and skilled workers (hundreds of thousands of Russians fled to exile to avoid mobilization or economic hardship) will likely drag on Russia’s economic prospects for years. By one estimate, Russia’s economy is nearly 20% smaller than it would have been had it not launched the war and faced sanctions (How Sanctions Have Reshaped Russia’s Future). Western officials assert that sanctions have degraded Russia’s military-industrial capacity – for instance, its tank factories and munitions plants struggle to obtain precision components and have resorted to cannibalizing electronics from appliances. However, sanctions alone have not stopped the war: Russia has adapted in some ways (finding new buyers for its oil, using currency controls to shore up the ruble, and leaning on reserves). In 2023, Russia even returned to modest GDP growth (about 1–2% by some estimates) driven by massive state spending on the war effort (How Sanctions Have Reshaped Russia’s Future). Still, this is unsustainable growth built on government debt and inventory depletion. Moscow’s increased military outlays led to a large budget deficit (roughly $47 billion in 2022, and growing) (Ukraine: what’s the global economic impact of Russia’s invasion? - Economics Observatory). By late 2024, Russia began cutting budgets for education, health, and other areas to funnel more into defense. Sanctions Implications: In the medium-to-long term, the sanctions are pushing Russia toward economic stagnation and technological regression. They have isolated Russia from Western capital and technology, forcing it into greater dependence on a few partners like China. The unified sanctions front also sends a strong signal: a blatant violation of international law will result in pariah status. However, a few major economies (notably China, India, and much of the Global South) have not sanctioned Russia, softening the blow. Going forward, enforcement and closing loopholes (such as sanctions evasion via third countries) remain a challenge for the West. Overall, sanctions have impaired Russia’s war-fighting ability and long-term economic health (How Sanctions Have Reshaped Russia’s Future) (How Sanctions Have Reshaped Russia’s Future), but they are a tool of pressure – not a quick fix. As of 2025, there is no indication that Putin is willing to alter course because of sanctions alone, especially as he can still fund the war through oil revenues (albeit reduced) and state coffers.

6. Humanitarian Impact

The human cost of the Ukraine war has been catastrophic. Civilians have borne a brutal burden from over two years of full-scale conflict. Casualties: According to the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), at least 12,000–13,000 Ukrainian civilians have been killed and around 30,000 injured since the February 2022 invasion began (Noting Ukraine’s People Have Endured Three Years of Relentless Death, Destruction, Displacement, Senior Official Tells Security Council ‘It Is High Time for Peace’ | Meetings Coverage and Press Releases). This includes more than 700 children among the dead or wounded. These figures only count verified incidents – the U.N. acknowledges the actual toll is undoubtedly higher, especially in areas like Mariupol or other zones that were under heavy bombardment where data is incomplete. Cities and towns reduced to rubble by fighting (Mariupol, Severodonetsk, Bakhmut, and others) suggest thousands more unrecorded civilian deaths. On top of this, military casualties on both sides are immense. Western officials have estimated that each side has suffered well over 100,000 personnel killed or injured by the end of 2023, figures that recall the attrition of World War I. In one estimate, Russian forces (including separatists and Wagner mercenaries) may have had on the order of 200,000–250,000 killed or wounded, while Ukraine’s military casualties are somewhat lower but still extremely high (Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, February 24, 2025 | Institute for the Study of War). These numbers are contested and not officially confirmed, but illustrate the scale of bloodshed in Europe’s deadliest conflict since World War II.

Displacement Crisis: The war triggered Europe’s largest refugee wave since WWII. Over 6.9 million Ukrainians – mostly women and children – have fled the country as refugees, primarily to neighboring European states (Poland, Germany, Czechia, etc.) (Noting Ukraine’s People Have Endured Three Years of Relentless Death, Destruction, Displacement, Senior Official Tells Security Council ‘It Is High Time for Peace’ | Meetings Coverage and Press Releases). Many have been granted temporary protection status in the EU, allowing them access to housing, jobs, and schools abroad. In addition, roughly 3.6 million people are internally displaced (IDPs) within Ukraine, having fled their homes for safer regions but remaining inside the country (Noting Ukraine’s People Have Endured Three Years of Relentless Death, Destruction, Displacement, Senior Official Tells Security Council ‘It Is High Time for Peace’ | Meetings Coverage and Press Releases). At the height of the war’s first phase, the number of IDPs was even higher (over 7 million internally displaced in mid-2022), but some have since returned to their home areas when fighting moved or after Russians were pushed out. All told, around 10 million Ukrainians remain uprooted from their homes due to the conflict (Noting Ukraine’s People Have Endured Three Years of Relentless Death, Destruction, Displacement, Senior Official Tells Security Council ‘It Is High Time for Peace’ | Meetings Coverage and Press Releases). This mass displacement has caused immense social upheaval – families separated, communities torn apart, and great strains on host countries and Ukrainian public services. Nonetheless, international humanitarian response (from governments, NGOs, and U.N. agencies) ramped up to assist refugees and IDPs with shelter, medical care, and schooling for children. Ukraine’s neighbors, particularly Poland, have absorbed millions of refugees with remarkable generosity (often local families hosting Ukrainians). Still, many displaced face uncertainty, trauma from the war, and the challenge of rebuilding their lives away from home.

Civilian Infrastructure and Living Conditions: The war has devastated Ukraine’s infrastructure and civilian life. Russian forces have repeatedly and deliberately struck non-military targets. The U.N. and human rights groups cite mounting evidence of war crimes by Russian troops – including indiscriminate shelling of populated areas, willful killings of civilians, torture, and sexual violence (U.N. rights office cites growing evidence of war crimes in Ukraine | Reuters) (U.N. rights office cites growing evidence of war crimes in Ukraine | Reuters). Entire towns like Mariupol, Popasna, and Soledar have been essentially wiped off the map by bombardment. Critical infrastructure has been a target: Russia’s campaign of missile strikes since October 2022 damaged about 50% of Ukraine’s power grid, causing widespread electricity and heating outages. For three consecutive winters, millions of Ukrainians have had to endure rolling blackouts and frigid temperatures as crews race to repair power stations and lines after each wave of attacks (Noting Ukraine’s People Have Endured Three Years of Relentless Death, Destruction, Displacement, Senior Official Tells Security Council ‘It Is High Time for Peace’ | Meetings Coverage and Press Releases). The attacks on energy infrastructure, which continued into 2023/24, at times left 10+ million people without power or heat in the dead of winter. The healthcare system has likewise suffered – the World Health Organization has verified over 790 attacks on hospitals and healthcare facilities since the invasion (Noting Ukraine’s People Have Endured Three Years of Relentless Death, Destruction, Displacement, Senior Official Tells Security Council ‘It Is High Time for Peace’ | Meetings Coverage and Press Releases). In occupied areas, there have been reports of lack of basic services and even forced deportations of civilians (including thousands of children) to Russia, raising concerns of ethnocide. Mines and unexploded ordnance contaminate vast swaths of land (an estimated 174,000 square kilometers, nearly a third of Ukraine, may require de-mining), posing a threat to civilians now and for years to come.

Humanitarian Response: International humanitarian organizations (U.N. agencies like UNHCR, WFP, ICRC, and numerous NGOs) are active across Ukraine and neighboring countries, providing emergency relief. According to the U.N., about 14.6 million people in Ukraine currently need humanitarian assistance such as food, water, healthcare, and shelter (War in Ukraine | Global Conflict Tracker). The Ukrainian government, despite the war, continues to deliver pensions and social services where possible and coordinate aid distribution. However, conditions in some Russian-occupied areas are largely unknown, as humanitarian access is mostly blocked by occupation authorities. There have been instances of humanitarian corridors for civilian evacuations (e.g., from Mariupol’s Azovstal plant in May 2022, from Sievierodonetsk in June 2022), but often agreements have broken down and evacuating civilians safely has been perilous. The shelling of a maternity hospital in Mariupol in March 2022 and a rocket strike on a packed Kramatorsk train station in April 2022 (which killed dozens of evacuees) are grim reminders of the dangers. Atrocities: Reports of atrocities continue to surface – summary executions of civilians in Bucha and other occupied towns in 2022, the bombing of a theater sheltering children in Mariupol (killing hundreds), torture chambers uncovered in liberated areas like Izium and Kherson, and the deadly missile strike on a civilian convoy in Zaporizhzhia in September 2022, among others. A U.N. investigative commission stated in 2023 that Russia’s attacks on civilians (apartment blocks, shopping centers, railway stations, etc.) may constitute crimes against humanity, due to their systematic nature. Ukraine has been documenting these crimes rigorously, and the International Criminal Court issued arrest warrants in 2023 for Russian officials (including for the unlawful deportation of Ukrainian children to Russia). The toll on children is particularly harsh – beyond those killed or injured, millions have had their education disrupted (many schools were damaged or forced to hold classes online or in bunkers), and countless kids suffer psychological trauma.

In summary, the humanitarian impact of the war is enormous and growing. A large portion of Ukraine’s 44 million population has been thrust into hardship. Cities lie in ruins; families are grieving lost loved ones; and an entire generation of Ukrainian children is scarred by war. The conflict has also caused a global humanitarian ripple effect – by disrupting Ukraine’s grain exports, it contributed to higher food prices that worsened hunger in parts of Africa and the Middle East in 2022. The war’s human suffering is incalculable, and addressing the needs of the victims – both now and in post-war reconstruction – will be a major international challenge.

7. Economic Consequences

Impact on Ukraine’s Economy: The war has devastated Ukraine’s economy, undoing decades of development. In 2022, Ukraine’s GDP contracted by about 30–35%, the deepest economic collapse in its history (Ukraine: what’s the global economic impact of Russia’s invasion? - Economics Observatory). This freefall was driven by the massive disruption of production, trade, and investment caused by the invasion – a significant portion of Ukraine’s industrial and agricultural base lies in war-torn areas or under occupation. The World Bank estimates Ukraine’s economy shrank by roughly one-third in 2022, with only a weak recovery (near 0%–2% growth) projected in 2023–2024 (Ukraine: what’s the global economic impact of Russia’s invasion? - Economics Observatory). Sectors like steel manufacturing (centered in Mariupol), coal mining, and machinery have been crippled or lost to occupation. Agriculture, which normally accounts for about 12% of GDP and a major share of exports, has been especially hard-hit – millions of hectares went unplanted in 2022–23 due to fighting and high fuel prices, and the blockade of Black Sea ports initially left last year’s harvest stuck in silos. The poverty rate in Ukraine spiked from 5% to 24% in 2022, pushing an additional 7 million Ukrainians into poverty virtually overnight (Ukraine: what’s the global economic impact of Russia’s invasion? - Economics Observatory). Inflation exceeded 20% as supply chains broke down and the government had to print money to cover defense spending. The national currency (hryvnia) depreciated by over 25% in 2022. To keep the economy afloat, Ukraine’s government leaned heavily on international financial aid – receiving tens of billions in grants/loans from the U.S., EU, IMF, and others to pay salaries and stabilize the budget. Despite the war, the government has managed to keep core functions running (tax collection, pensions, etc.), but fiscal pressures are extreme: Ukraine’s budget deficit neared $5 billion per month in late 2022. Physical damage is massive – as of mid-2023, the World Bank assessed over $140 billion in infrastructure damage (roads, bridges, buildings) and an even higher cost when including wider economic losses. Key export infrastructure like Mariupol port (formerly a crucial steel export hub) and Azovstal steel plant have been destroyed. The partial reopening of Black Sea grain exports in mid-2022 provided some relief (Ukraine shipped over 30 million tons of grain under the grain deal before it ended), but Russia’s exit from the deal in 2023 and continued threats to shipping have again constrained exports. The war has forced Ukraine to reorient trade to the EU via land routes and Danube River ports – helpful, but not as efficient as Black Sea shipping.

Looking forward, Ukraine faces a long road to recovery. The Kyiv School of Economics estimated total economic losses from the war (damages + lost output) could exceed $600 billion if the war continues into 2025. Reconstructing housing, infrastructure, and industries in liberated areas is a monumental task – cities like Mariupol or Sievierodonetsk will essentially need to be rebuilt from scratch. Donor conferences have been convened (e.g. Lugano 2022, London 2023) to plan for Ukraine’s reconstruction, and the World Bank, EU, and UN have drafted assessments. An initial estimate in March 2023 put the cost of reconstruction at $411 billion and rising (Ukraine: what’s the global economic impact of Russia’s invasion? - Economics Observatory). Much of this will have to be financed by international aid and perhaps reparations or frozen Russian assets (a topic under legal debate). Ukraine’s post-war recovery prospects are actually positive if peace is achieved and massive investments flow – given its educated workforce, rich farmland, and potential EU accession – but in the meantime, the country is operating in a state of economic emergency.

Impact on Russia’s Economy: Russia’s $1.7 trillion economy initially weathered the shock of war and sanctions better than many expected, but the war has set its economic trajectory back by years. In 2022, Russia’s GDP officially fell by about 2.1% (How Sanctions Have Reshaped Russia’s Future) – a relatively modest drop compared to some forecasts of a 10%+ collapse. Early in the war, a spike in global oil and gas prices actually boosted Russia’s export earnings, cushioning the economy and allowing Putin to maintain war spending. Additionally, swift actions by Russia’s Central Bank (such as capital controls and hiking interest rates) and continued trade with non-Western countries helped stabilize the financial system after the initial sanction blows. By mid-2022 the ruble had surprisingly rebounded to become one of the world’s best-performing currencies, largely due to strict currency controls and strong export revenues. However, these headline figures masked deeper stresses. Underneath a veneer of stability, Russia’s economy has been forced into a dramatic restructuring and isolation. Over 1,000 foreign companies pulled out of Russia, leading to loss of investment, technology, and jobs. Critical imports of high-tech components were largely cut off, undermining industrial production – for example, Russian car manufacturing plummeted by 50% in 2022 because parts were unavailable and Western automakers left (Ukraine: what’s the global economic impact of Russia’s invasion? - Economics Observatory). To keep factories running, the Kremlin has had to turn to “parallel imports” (smuggling goods through third countries) and substitute Western suppliers with Chinese, Iranian, or domestic ones of often lower quality.

As the war dragged into 2023, the cumulative effects of sanctions became more pronounced. Russia shifted into a “guns over butter” economy, channeling state resources to the military at the expense of civilian sectors. Military expenditures reportedly surged to about one-third of the federal budget in 2023, contributing to a growing budget deficit (Ukraine: what’s the global economic impact of Russia’s invasion? - Economics Observatory). By early 2023, Russia’s oil revenues began to decline as the EU oil ban and G7 price cap kicked in, forcing Russia to sell oil at discounts of 20-30% to market price. In the first half of 2023, Russia’s government oil revenues were down about 50% year-on-year. Simultaneously, war costs spiked due to the expensive winter bombing campaign and the need to equip freshly mobilized troops. This pushed Moscow’s budget into the red – Russia posted a budget deficit of 2.3% of GDP in 2022 and it continued to widen in 2023 (Ukraine: what’s the global economic impact of Russia’s invasion? - Economics Observatory). The government tapped its rainy-day National Wealth Fund for war spending and to prop up companies hit by sanctions. The labor force also shrank: hundreds of thousands of mainly young professionals emigrated to escape sanctions or mobilization, and as of 2023 the military had absorbed perhaps 300,000 additional men (through mobilization and recruitment), creating labor shortages in other parts of the economy (How Sanctions Have Reshaped Russia’s Future).

By late 2023, cracks were showing: the ruble weakened past 100 to the dollar in August 2023, prompting the central bank to hike interest rates to 12%, then 15%, and eventually 21% in 2024 to combat inflation and support the currency (How Sanctions Have Reshaped Russia’s Future). Russian officials started to admit difficulties; the Economy Minister projected a meager 1% GDP growth for 2024 and high inflation due to “structural adjustments.” Analysts note that while Russia has adapted in the short term, its long-term economic outlook is bleak if the war and sanctions persist (How Sanctions Have Reshaped Russia’s Future). The country is expending its military stockpiles and financial reserves much faster than it can replace them. Key industries face bottlenecks – for instance, Russia had to drastically cut production of cars and some electronics for civilians to divert components to military use. The loss of Western technology and investment could set Russia’s technological level back by years. Additionally, Russia’s pivot to Asian markets makes it a junior partner to China; for example, Russia is now selling oil to India and China at substantial discounts, and it has become more dependent on imports of Chinese manufactured goods. Putin’s own advisers have likened the situation to the 1980s Soviet economy – a heavy focus on military output while consumer welfare stagnates. In effect, Russia is sacrificing future economic growth for the sake of sustaining the war. The World Bank and IMF expect Russia’s economy to stagnate near zero growth in 2024–2025 if current trends continue. In sum, Russia’s economy has been profoundly reshaped by the war: it proved resilient enough to avoid collapse in 2022, but it has entered a period of decline and austerity. The true cost will become more evident over time – reduced living standards for ordinary Russians (real incomes and consumption are down), loss of competitiveness and innovation, and a potential widening gap with the global economy that Russia has now largely isolated itself from (How Sanctions Have Reshaped Russia’s Future). Yet, as long as the Kremlin can continue funding its military and suppressing dissent, these economic troubles have not translated into policy change regarding the war.

Global Economic Repercussions: The Ukraine war has significantly affected the global economy, primarily by disrupting energy and food markets and fueling inflationary pressures worldwide. In 2022, the war delivered an inflationary shock just as the world was emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic. Russia was a top exporter of oil, gas, and coal, while Ukraine was a top exporter of grains (corn, wheat) and vegetable oils – the war perturbed these supplies dramatically. Global oil prices spiked above $120 per barrel in March–June 2022 on fears of Russian supply loss. European natural gas prices hit record highs (over 10 times their normal level) in 2022 as Russia cut off gas flows via pipelines (Nord Stream, etc.) in retaliation for sanctions (Energy & Climate Intelligence Unit | Two years of Russia’s war on…) (Energy & Climate Intelligence Unit | Two years of Russia’s war on…). This surge in energy prices drove inflation to multi-decade highs in many countries. By mid-2022, global inflation had roughly tripled from pre-pandemic levels, reaching around 9% on average – with even higher rates in Europe due to energy costs (The Long-lasting Economic Shock of War). Governments had to shield consumers with subsidies and price caps (for example, European countries spent hundreds of billions on energy relief measures). High fuel costs also increased production and transportation costs across the board.

The food supply shock was likewise severe. Ukraine normally feeds hundreds of millions of people globally with its grain exports, especially in Africa and the Middle East. In the months following the invasion, Ukraine’s seaborne grain exports plummeted to near zero as Russia blockaded the Black Sea. This helped push global food prices to an all-time high in May 2022. Countries that relied on affordable Ukrainian wheat – like Egypt, Lebanon, and Yemen – faced rising bread prices and worsening food security. By late 2022, the U.N. warned that an additional 70 million people worldwide could be pushed into acute hunger due to the war’s impact. Although the Grain Initiative from July 2022 partially eased this (with Ukraine shipping grain from Odesa again), prices remained volatile. The war has “greatly compounded” existing global economic woes like rising poverty and hunger (The Long-lasting Economic Shock of War) (The Long-lasting Economic Shock of War). For instance, the World Food Programme noted that the fallout from the war in Ukraine (along with other conflicts and climate issues) has kept food prices at crisis levels in many poor countries (A global food crisis | World Food Programme).

Beyond energy and food, the war has accelerated geopolitical shifts in trade. Europe undertook a rapid pivot to replace Russian energy: by winter 2022/23, the EU had found alternative gas supplies (LNG imports from the U.S. and Qatar, and pipelines from Norway/Azerbaijan) and filled storage, enabling it to get through the winter despite Russia effectively turning off the gas taps. This diversification has permanently changed global LNG flows and made Europe more energy independent from Russia, albeit at higher cost. On the flip side, Russia deepened trade with Asia – for example, by mid-2023 China became the largest importer of Russian oil and gas, and India went from near-zero Russian oil imports to buying over 1 million barrels/day. The war has also forced countries to re-evaluate defense spending and supply chains – Europe is upping defense budgets (Germany’s Zeitenwende policy, etc.), which has economic implications (more military procurement, potentially less social spending).

In financial markets, the war initially sent investors to safe havens: stock markets dipped and commodity prices jumped. Over time, markets adjusted, but the uncertainty (especially about nuclear risks or escalation beyond Ukraine) remains a concern that can rattle global confidence. The war has arguably sped up the fragmentation of the global economy into blocs. U.S.-China tensions have grown as China supports Russia’s narrative; meanwhile, Western democracies have grown more unified. Issues like food security, energy security, and high inflation triggered by the war have become top agenda items in international forums like the G20. For example, at G20 meetings in 2022 and 2023, many countries emphasized how the war in Ukraine was undermining global economic recovery by driving up prices (The Long-lasting Economic Shock of War~).

One positive effect is that Europe’s rush to replace Russian gas led to an unprecedented build-out of renewable energy and energy-saving measures. EU countries accelerated green energy projects and set targets to cut reliance on fossil fuels faster, partly for energy security reasons. In the long run, this could spur cleaner energy transitions. In the short run, however, Europe had to fall back on some dirty fuels (like coal) and pay steep prices for LNG, which hit energy-intensive industries.

Bottom line: The war in Ukraine has been a significant headwind to the global economy. It exacerbated inflation, slowed growth (the IMF trimmed global growth forecasts for 2022–2023 repeatedly due to war impacts), and required costly government interventions to mitigate. Countries already reeling from the pandemic found their fiscal capacities further strained. Developing nations dependent on food and fuel imports suffered the most. By 2023, inflation began to ease as central banks raised interest rates and as markets adapted (with grain corridors and new energy trade flows), but the war’s economic aftershocks are still being felt. The conflict underscores how interconnected the world is – a war in Europe triggered everything from higher grocery bills in Africa to heating crises in Europe and new economic alliances in Asia. Should the war continue or escalate, these economic disruptions are likely to persist or worsen, whereas a peace (and lifting of Russia sanctions) could eventually alleviate some pressures (though not before major rebuilding in Ukraine).

8. Future Projections and Scenarios

As the war grinds on into its third year, observers are analyzing possible future trajectories. Two critical variables will shape what comes next: the level of international support for Ukraine and the political will/ability of Russia to continue the fight. Here we examine how varying levels of support – especially from the United States – could affect the conflict, and what experts foresee in the coming months.

Ukraine’s Ability to Sustain Defense (Especially Without U.S. Support): Western support is literally fueling Ukraine’s war effort. If that support were significantly reduced or cut off, it would severely threaten Ukraine’s capacity to carry on. Currently, Ukraine receives not only advanced weapons but also financial aid that covers a huge portion of its budget (paying soldiers, keeping the lights on, etc.). The United States is the single largest supplier of military aid to Ukraine (about half of all heavy weapon deliveries), providing systems that European allies either cannot supply in sufficient numbers or don’t have at all – such as long-range HIMARS rockets, Patriot air defense batteries, and large quantities of artillery shells. If U.S. military aid ceased, Ukraine would very quickly face shortages of ammunition and critical equipment, since European stockpiles and production capacity are limited by comparison (Opinion: Could Ukraine survive a JD Vance vice presidency?). For instance, European NATO states combined currently cannot produce artillery rounds at the rate Ukraine expends them, nor do they have spare Patriot missile systems to cover Ukraine’s skies if the U.S. withdrew its units. Ukraine does have some self-sustaining capacity (it has its own defense industry for rifles, some armored vehicles, etc., and is developing drones), but it is not yet capable of fully equipping an army for high-intensity warfare without foreign help. Analyses indicate that Ukraine could still fight on for a time even without new U.S. aid, thanks to equipment already delivered and financial assistance from Europe, but its effectiveness would gradually diminish (Opinion: Could Ukraine survive a JD Vance vice presidency?). The Kiel Institute’s tracking shows that from Feb 2022 to April 2024, the U.S. accounted for about 40% of total committed aid to Ukraine, with Europe and other allies providing 60% (Opinion: Could Ukraine survive a JD Vance vice presidency?). This suggests Europe theoretically could increase its support to compensate for a drop in U.S. aid. Indeed, the EU has set up a multi-billion Euro fund to jointly procure ammunition for Ukraine and is considering using frozen Russian assets for financing. Europe’s economic size (over $20 trillion GDP) dwarfs Ukraine’s needs, so financially Europe could step up if political will exists (Opinion: Could Ukraine survive a JD Vance vice presidency?). However, the issue is not just money – it’s also military capacity. Key U.S.-supplied capabilities (Patriot air defense, HIMARS/ATACMS rockets, satellite intelligence, Abrams tanks, etc.) cannot be easily replaced one-for-one by Europeans in the short term (Opinion: Could Ukraine survive a JD Vance vice presidency?). A recent study found that if the U.S. withdrew from Europe entirely, the EU would need to spend hundreds of billions and raise hundreds of thousands of additional troops to credibly deter Russia (Defending Europe without the US: first estimates of what is needed) – underscoring how reliant Europe is on U.S. military power. Thus, in a scenario where U.S. support wanes (for example, due to domestic political shifts in Washington), Ukraine would become far more dependent on a coalition of European and other partners like the UK, Poland, Germany, France, Canada, etc. Those partners have pledged that they will “not let Ukraine fail,” but it might take time for them to organize replacements for U.S. contributions (both weapon systems and funding). We could expect Ukraine in that case to adopt a more defensive posture – focusing on holding existing lines rather than large-scale offensives – to conserve resources. Ukraine has also built up some strategic reserves (for instance, by early 2025 it has been promised around 50–60 modern Western tanks and dozens of advanced air defenses, and it holds significant currency reserves of its own) (Opinion: Could Ukraine survive a JD Vance vice presidency?) (Opinion: Could Ukraine survive a JD Vance vice presidency?). Those could allow it to endure for perhaps several months even if new aid slowed. However, as stocks of precision munitions run down and if no new aid arrives, Ukraine’s vulnerability would sharply increase – especially to Russian airpower (if air defenses lack missiles) and in its ability to support any counterattacks (Opinion: Could Ukraine survive a JD Vance vice presidency?). The risk then is that Russia, sensing weakening resistance, could go back on the offensive more boldly, or Ukraine might be pressured into a truce that favors Moscow.

Conversely, if robust U.S. support continues or even increases, Ukraine can sustain its military operations and possibly improve its capabilities further. There are proposals in Washington and European capitals to supply even more advanced arms (such as Western fighter jets – which is already in the works – and longer-range missiles or more tanks). The delivery of such systems in significant numbers could enhance Ukraine’s ability to break through Russian lines or defend against any new Russian offensives. For example, if by late 2025 Ukraine fields Western-trained F-16 pilots with modern jets, its air force could better contest the skies. Continued aid also enables Ukraine to slowly but steadily expand its drone and missile campaign against Russian military targets in occupied territory and even in Russia (as seen by the increasing Ukrainian drone strikes on bases as far as deep Russia in 2024). Essentially, as long as Western aid remains strong, Ukraine is not at risk of collapse – it will have the means to keep resisting and gradually wear down the Russian military.

Scenarios for 2024 and Beyond: Military and political experts outline a few broad scenarios for the next phase of the war:

Stalemate / War of Attrition (Status Quo Scenario): Many analysts foresee that the most likely near-term scenario is a continued stalemate, where neither side can land a decisive blow. Both Russia and Ukraine might make minor territorial gains in localized offensives, but no breakthrough sufficient to end the war. This scenario assumes Western aid stays steady but not dramatically expanded (meaning Ukraine can hold the line but not easily evict a well-dug-in enemy), and Russia manages to avoid internal collapse. In this case, the front might look roughly the same in a year’s time, with ongoing fighting and high casualties but little change on the map. A drawn-out war of attrition could last into 2025 or beyond (The Russo-Ukrainian War: A Strategic Assessment Two Years into the Conflict | AUSA). The toll on Ukraine would be enormous, but its army is motivated to keep fighting as long as support comes. For Russia, a prolonged war might be tolerable to Putin if he judges time is on his side (waiting for Western unity to fracture). The risk, however, is that time could also further degrade Russia’s military while Ukraine gets stronger. A protracted stalemate could eventually force both sides to consider a freeze or armistice (like a new demarcation line), but at this point neither Moscow nor Kyiv is ready to accept a frozen conflict as a formal outcome.

Escalation by Russia (Worst-Case Scenario): If Putin grows desperate (for example, if Ukrainian offensives threaten to eject Russian forces from a key area like Crimea or if internal pressures mount), Russia could escalate further. This could mean more indiscriminate destruction in Ukraine or even the use of unconventional weapons. Western intelligence regards the chance of Russia using a tactical nuclear weapon as low but not zero, particularly if Putin perceives an existential threat. Such an escalation would be intended to shock Ukraine and its backers into halting operations. So far, Russia’s escalatory steps have been relatively contained (mobilization of draftees, intensified bombing). But analysts warn that nuclear saber-rattling remains a possibility if Russia faces outright defeat. Another form of escalation could be opening new fronts – e.g., a second invasion from Belarus towards western Ukraine (deemed unlikely due to earlier failures and Belarusian reluctance) or more aggressive moves against NATO (such as sabotage or cyberattacks). NATO has been clear that any attack on allied territory would trigger a robust response; this deterrence has held so far.

Ukrainian Breakthrough (Best-Case for Ukraine): In a scenario where Western military aid significantly increases – for instance, if Ukraine were provided with a large fleet of modern tanks, armored vehicles, ample ammunition, ATACMS long-range missiles, and maybe even Western aircraft in meaningful numbers – Ukraine could potentially achieve a major breakthrough on the battlefield in 2024. This might involve punching through Russian lines in Zaporizhzhia and advancing toward the Azov Sea, effectively severing Russia’s land bridge to Crimea. If Ukrainian forces managed to retake a strategic city like Melitopol or Mariupol, it would be a game-changer. That could put Crimea within range of direct ground attacks and dramatically weaken Russia’s strategic position. A cascade of victories might even threaten the collapse of Russian frontline armies. While this scenario is aspirational, Ukrainian commanders believe with enough force concentration and continued degradation of Russian logistics (via HIMARS strikes, partisan sabotage, etc.), it’s feasible. The political result of a Ukrainian breakthrough could be to force Moscow into seriously negotiating or even lead to regime instability in Russia. However, even Ukrainian optimists usually stop short of assuming they can militarily liberate every inch of territory in the near term. Crimea, for example, is heavily defended and of huge symbolic importance to Putin. A best-case military outcome for Ukraine might be a sweeping southern offensive that compels Russia to sue for peace, perhaps giving up the newly occupied territories (Donbas and south) but trying to keep Crimea under some negotiated arrangement.